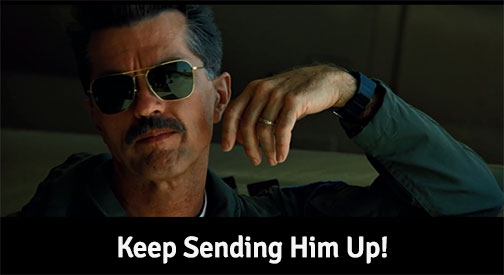

(And the Art Of Keep Sending Them Up)

Anyone who practices their craft fails. We'd all love to learn from other people's mistake, but when you become really good at something you slowly start experimenting with the basic laws of the field. The laws that not many before you have broken. Suddenly, you are in unchartered territories. The mistakes you make now are not mistakes that a lot of others have made; and there are not many examples to learn from. Your only option is taking small baby steps of experimentation and embracing failure when it shows up.

Awesome organizations and companies usually become awesome by embracing craftsmen who have the courage to charter into this unchartered territories, take calculated risk, sometimes fail and then look back and learn from the stories of these failures.

Most organization obsessed with the line of best fit may not directly fire someone for failing in a venture or a project, but penalties of failures are usually high in these cultures.

Fail a project once and see how your company quietly removes you from the next mission critical project the organization is going to take up. Go through a rough time in your personal life, slip up on a couple of tasks and see how the next collection of mission critical tasks are quietly and politely passed on to someone else.

Embracing failures and putting your trust on the best of your team members is not something that requires deep intellectual and philosophical conversations. Most of the times, a simple mind-set of "keep sending him up" is good enough:

Trust in the best of people you work with isn't conveyed by delivering talks of embracing failure in company get together and all-hands-meetings. This trust is often tested by how much responsibility you give to the best of your builders when they have failed colossally. The story Pixar and how Steve Jobs, Yet Catmull and John Lesseter put their faith in Brad Bird is a classic story of this trust rightly placed. Author Peter Sims tells the story in his book, Little Bets - How breakthrough ideas emerge from small discoveries. Peter explains:

Perhaps no story I heard about Pixar exemplifies the growth mind-set at the company as clearly as that of the making of The Incredibles. When Pixar recruited Brad Bird as a director, Bird was coming off directing a Warner Brothers film called The Iron Giant that was a box-office disappointment. Pixar, meanwhile, already had three big hits. Yet Catmull, Steve Jobs, and John Lasseter (Pixar’s creative lead) told Bird, "The only thing we're afraid of is complacency — feeling like we have it all figured out.

We want you to come shake things up. We will give you a good argument if we think what we’ re doing doesn't make sense, but if you can convince us, we'll do things in a different way , "Bird told Stanford professors Robert Sutton and Hayagreeva Rao. "For a company that has had nothing but success to invite a guy who had

just come off a failure and say , 'Go ahead, mess with our heads, shake it up'; when do you run into that?"

And this trust is not just about words and tag lines like 'shake it up'. It is about empowering your builders. And so when you do place this trust in your builders, they will in return expect that you put your money where you mouth is; just what Bird expected from Pixar:

Bird would soon test that invitation with his ambitious ideas for The Incredibles. His vision for the film had so many characters and sets that members of Pixar’s technical team believed it would take ten years and cost $500 million to make. "How are we going to possibly do this? " they asked.

But continue this trust and it is contagious. It even helps you find the rebels and the troublemakers in your own organization who have the potential to produce outputs your organization has never ever produced before. How the story of making of Incredibles ends is a classic example of this:

A determined Bird implemented a number of changes in Pixar's process in order to do so, from which Pixar learned a great deal. In order to help shake things up, one thing Bird did was to seek out people within Pixar whom he described as black sheep, whose unconventional views could help find solutions to the problems. "A lot of them were malcontents because they saw different ways of doing things," Bird said. "We gave black sheep a chance to prove their theories, and we changed the way a number of things are done here."

Among those changes, they altered the approach to storyboards and computer graphics standards. For example, they created what Bird called super elaborate storyboards that emulated camera movement to show which parts of the images of scenes needed to be perfect (e. g. , have fine-grained detail) and which ones didn't. This allowed the animators to focus their efforts more on the aspects of the movie that required the most attention, such as the action scenes, which were the primary drivers of the film's plot.

They eventually made the film for less money per minute than Pixar's previous movie, Finding Nemo, despite significantly more complexity, including three times as many sets.

"You want people to be involved and engaged," Bird said. "What they have in common is a restless, probing nature: 'I want to get to the problem. There's something I want to do. ' If you had thermal glasses, you could see heat coming off them.

The story is inspirational and like most stories of genuine builders it's not made up of deep philosophies. Just a simple idea of placing your trust in people who deserve your trust and empowering them to make a difference and then if they fail once in a while - keep sending them up there.

How does that stack up with your organization? How does that stack up with your own personal management style? How do you deal with otherwise immensely talented and hard working people in your team who are having a rough time in their lives or have just been hit by a colossal failure?

Do you write them off and in an attempt to replace them like a cog in a machine slowly hand over their responsibilities over to other cogs, or do you place your trust in them? Do you see them as losers or do you see them as individuals who are capable of listening to the stories of their own failures and learning from these stories?

In really simple words - do you keep sending them up there?

Because if you don't the loss is all yours - Your best builders are what makes or breaks your organization. Of course they can recover from failures, but when you start seeing them as losers because of a failure or two... eventually, both you and your organization loose.

Comments are closed.